Alligators of South Carolina and Georgia

The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is a large reptile native to the southeastern United States. Once listed as federally endangered, this species has made a remarkable recovery and is now common across much of its range. It remains federally listed as threatened due to its close resemblance to the endangered American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus).

Alligators are long-lived animals, with life spans that may exceed 60 years. As ectotherms (“cold-blooded”), they cannot regulate their body temperature internally and instead rely on their environment. They are often seen basking on riverbanks or pond edges to warm themselves. During hot summer days, alligators sometimes rest with their mouths open, a cooling behavior comparable to panting in dogs. Ecologically, they are top predators and ecosystem engineers: by digging “gator holes” that retain water during droughts, they provide critical refuges for fish, amphibians, and other wildlife.

Range and Habitat:

American alligators occur along the Atlantic Coastal Plain from Florida to coastal North Carolina, and west along the Gulf Coast into Texas. They are restricted to the Coastal Plain, which includes the Central Savannah River Area of Georgia and South Carolina. In South Carolina, individuals over 13 feet in length have been documented.

Preferred habitats include swamps, rivers, lakes, ponds, and slow-moving streams. Females and juveniles also use seasonal wetlands such as Carolina Bays. Though primarily a freshwater species, alligators occasionally venture into brackish estuaries or salt marshes. On the Savannah River Site, they are abundant in the Savannah River, its swamps and tributaries, and in reservoirs such as L-Lake and Par Pond.

Reproduction:

Alligators are active year-round, but activity peaks during the warmer months in Georgia and South Carolina. Breeding season begins in May, when males produce deep, resonant “bellows” to attract females and advertise their presence to rival males. Courtship is elaborate, involving head-slapping on the water’s surface, body posturing, rubbing of snouts and backs, bubble blowing, vocalizations, and chemical signals (pheromones).

By June, mating has occurred and females begin constructing mound nests of vegetation, mud, and debris. The rotting vegetation generates heat, which helps incubate the eggs. From late June to mid-July, females deposit 20–60 hard-shelled white eggs, each about 3 inches long and resembling a goose egg. Mothers guard the nest during the ~65-day incubation period, defending it against predators.

When the eggs hatch, the female assists by uncovering the nest, gently opening unhatched eggs, and carrying the young to water. She may continue to protect her hatchlings aggressively for over a year. Without maternal care, most young do not survive predation.

Growth is slow; hatchlings typically add 3–8 inches per year. At around 6 feet in length, they are considered adults.

Did you know?

- Ancient lineage: Alligators and their relatives are the last living reptiles closely related to dinosaurs. Their closest modern relatives are birds.

- Two species worldwide: Only two alligator species exist today. The American alligator (A. mississippiensis) and the Chinese alligator (A. sinensis).

- Alligator vs. Crocodile: Alligators have broad, rounded snouts, while most crocodiles have longer, pointed snouts. In the U.S., crocodiles are limited to extreme south Florida, whereas alligators thrive in cooler climates across the Southeast.

- Efficient metabolism: As ectotherms (“cold-blooded”), alligators require little food. An 800-lb alligator may eat less in a year than a 100-lb dog.

- Senses: Alligators have relatively poor eyesight, but their eyes are protected by a transparent nictitating membrane that allows them to see underwater. Their ears, located just behind the eyes, are highly sensitive to both sound and water vibrations.

- Dancing water: During breeding season, male alligators produce powerful bellows that cause the surface of the water to vibrate and “dance.”

- Temperature decides sex: The sex of hatchlings is determined by nest temperature: cooler nests produce mostly females, while warmer nests produce mostly males.

- Built-in ecosystem engineers: By digging “alligator holes” that hold water during droughts, they create critical wetland refuges for fish, turtles, birds, and other wildlife.

- Super swimmers: Alligators can hold their breath underwater for more than an hour by slowing their heart rate and conserving oxygen.

Prey:

American alligators are opportunistic predators. Adults feed on a wide variety of animals, including fish, turtles, wading birds, snakes, frogs, small mammals, and even smaller alligators. Juveniles primarily consume small fish and aquatic invertebrates. However, young alligators themselves are vulnerable to predation by raccoons, large snakes, turtles, wading birds, fish, and even crabs.

Research:

At the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory (SREL), American alligators have been studied for more than 35 years, making them one of the longest-monitored species at the site. Research has examined population size and distribution, genetic structure, long-term trends, activity patterns, growth and reproduction, diet and energetics, and responses to environmental changes such as reactor thermal effluent. Additional studies have focused on contaminant uptake, particularly radionuclides, and their impact on this long-lived reptile. Current work includes long-term mark-recapture surveys, analysis of mating systems and paternity, and investigations into the effects of contaminants on alligator health and conservation.

Alligator Management in South Carolina

Management Practices:

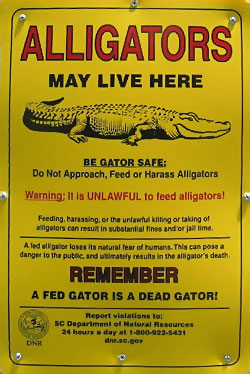

Alligators possess a strong homing instinct and have been documented returning to their original location even after being relocated more than 100 miles. Because of this remarkable navigational ability, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) has determined that relocation is ineffective and therefore illegal in the state. When an alligator is deemed a “nuisance,” it must be removed, and removal means it is euthanized by a licensed alligator control specialist.

In 1989, SCDNR created a nuisance alligator program that authorizes contracted trappers to remove 300–350 individuals annually. These removals target animals that:

- Exhibit aggressive behaviors toward humans or domestic animals

- Have become habituated to people, usually due to feeding

- Show signs of severe injury or illness

- Occupy recreational waters used primarily for swimming

In 2008, the alligator was legally classified as a game animal, and a tightly regulated hunting season was established. This is conducted as a quota hunt through an application and permitting system. Each successful applicant is allowed to harvest only one individual per season.

Conservation Challenges:

Although American alligator populations have rebounded from historic overharvesting—helped by supplemental farming practices and reduced harvest of wild individuals—new pressures are emerging. Expanding coastal development, along with the widespread use of stormwater lagoons on golf courses and residential properties, has increased the frequency of human–alligator interactions. Because relocation is not an option, property-owner complaints nearly always result in the animals’ removal from the population. Feeding by humans further exacerbates this problem, as habituated alligators are disproportionately targeted for removal.

Beyond human conflict, alligators also face direct habitat loss and environmental contamination. Pollutants such as mercury and pharmaceuticals have been shown to degrade water quality and cause physiological stress in exposed individuals.

Future:

The future of alligator conservation in South Carolina depends heavily on public understanding and cooperation. Long-term survival of the species requires continued management efforts, habitat protection, and most importantly, support from people living in alligator country to avoid feeding, harassing, or unnecessarily removing these ecologically important reptiles.

Send your suggestions, comments, or questions to: srel-herp-id@uga.edu.

Please include locality data for identifications.